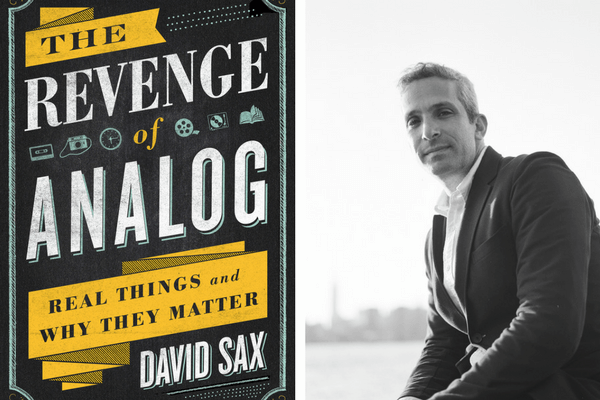

David Sax is an award-winning author and business journalist. Sax’s latest book, The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, was named by the New York Times and Inc. magazine as a “Best Book of 2016.” Sax’s book describes a surprising trend: businesses that have stayed with analog production are now making a comeback, despite all the attention on digital. Sax explores how a number of middle market companies, such as United Record Pressing in Nashville (which is taking advantage of the vinyl record boom) and Shinola in Detroit (a watch manufacturer), are leading analog’s resurgence.

What follows is an edited transcript; for the full version, listen to the Soundcloud podcast embedded below.

Why has the digital economy received so much attention from the media, while the analog economy gets relatively little?

Sax: We love a good, clean historical narrative, and the digital economy provides one. Old technology is always replaced by new technology. That’s innovation and that’s the road to success. The digital economy also offers these wonderful Cinderella stories. Companies like Facebook and Instagram and Uber, in a couple of years, can go from an entrepreneur having a single idea to being one of the largest, most powerful companies in the world.

The narrative for the analog economy is more reserved and that’s the nature of analog growth. You can’t build a billion-dollar manufacturing company overnight. It doesn’t scale as quickly, and it doesn’t provide that same clean narrative. How can middle market companies like Shinola be making money off watches when the watch is supposed to be dead?

Why hasn’t online retail, led by Amazon, displaced bricks-and-mortar retailers?

Sax: In a broader sense, e-commerce is still a relatively small percentage of retail sales, at around 10 percent. An online store is generally not the best way to sell things. In a [physical] store, for example, you can have a conversation with a staff person who might suggest a product and literally put that product into your hands. “Read this book. You should try on this shirt. You should check out these glasses.” This is a very personal, individualized, and human-centric form of retail, and that’s the core of what makes a good retail experience. It leads to higher sales, higher margin sales, and more sales per customer transaction than you would find online, which tends to be focused on pricing and selection. Now even Amazon is opening bricks-and-mortar stores, and it’s not because of nostalgia.

What are some challenges that analog middle market companies might face that digital firms don’t?

Sax: The disadvantages of the analog business are that you have to build a facility with physical materials, and staff it with human beings, and pay rent, buy real estate, get insurance, ship boxes, all of which have a cost. But that cost can be reflected in the price of the goods and built into the business model. In the digital world, it’s the model of venture capital-funded tech companies: create a product or service, get it out there to as many people as possible, then figure out how you’re going to make money off it or have someone buy you out.

In the digital world, you’re either going to be the top dog in your field (like Amazon or Google) or you’ll be the one that flames out and doesn’t exist anymore. It’s winner-take-all. The analog market allows for many more competitors of different sizes who can all coexist, compete with each other, work off each other, and build up the market together.

How do you compare analog companies with digital companies in terms of job creation?

Sax: Analog businesses require a greater range of skills. With United Record Pressing (URP), the nation’s largest record pressing company and a middle market company, they have an executive team, employees who are in recording, sound checking, and marketing. They also have high-skilled machinists, as well as people in the warehouse shifting boxes. There are drivers and janitors. You get the whole economic spectrum, from high-end white collar jobs to middle-income jobs to entry-level warehouse jobs that help support the entire community.

Contrast that with Spotify, a digital competitor of the vinyl record industry. They have high-end jobs for college-educated people {software developers] who are going to be earning high starting salaries. There’s not much below that. You have low-end jobs in digital too -- Uber drivers and Amazon warehouse workers. But you’re not going to have many mid-level digital jobs. So it’s middle market companies in analog industries that are serving us better in creating broad-based employment.

How has a thriving middle market company like Shinola built its business model around craftsmanship and “made in Detroit” messaging?

Sax: When you buy a Shinola watch for $800 to $1,000, and other goods they make such as journals and bicycles, they’re definitely priced higher than the [foreign] competition. What you’re paying for is the story of the manufacturing in Detroit and in America, as well as the story of the company and the benefits it brings to the Detroit community. That story is very marketable. Shinola has built its entire brand around that story, and found success.

What’s the potential for combining analog and digital?

Sax: The choice between analog and digital is very much a false, binary narrative. Businesses need every tool at their disposal to be successful. Sometimes that’ll be digital, sometimes analog. Blending analog and digital may be the most powerful tool of all.

There’s been an assumption that if you don’t move your entire organization to something digital, you’re a dinosaur. But sometimes it’s more efficient to use analog tools such as whiteboards, paper and pen, or in-person meetings where you turn off your phones. The most innovative companies going forward are the ones that take a good, hard look at where analog gives them an advantage, and where it complements digital, as well as where digital technology can help bring analog goods and services to the customer in a more efficient way.

What advice would you offer middle market leaders as they consider this “blended approach” to business growth?

Sax: Always keep in mind that we’re analog creatures in an analog world. We’re not living in some virtual simulation. Customers are always going to respond in a more meaningful and deeper way to interactions with physical goods and services. While it might appear that analog is less efficient than digital, analog can provide greater long-term value, can build deeper relationships, and can be more profitable.

Whenever a new digital technology promises to revolutionize an industry, I would advise all middle market leaders to assess the technology based on its own merits, but not be blinded by a pressure to be innovative. Sometimes innovation is more powerful in its analog form than in digital form. And sometimes it’s the opposite. And it may be that the blending of analog and digital provides the best way forward.