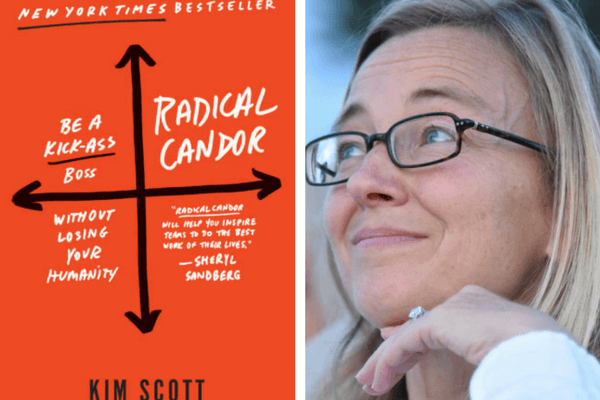

Kim Scott is the bestselling author of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity, and she doesn’t just write about leadership. Scott has held prominent leadership roles at Google (where she worked with Sheryl Sandberg) and Apple. Scott has also advised numerous Silicon Valley firms including Twitter, Dropbox, and many more. As co-founder and CEO of Candor, Inc, Scott currently helps managers implement the practices explained in her insightful and deeply-human bestseller, "Radical Candor." We caught up with her recently to talk about leading with “radical candor.”

How do you define "radical candor?"

Scott: Radical candor is about caring personally for people at the same time that you challenge them directly. So if you see somebody making a mistake, you tell them in a way that shows you care personally. The reason I call it “radical” candor is because it’s so rare. And I think it's rare because, when we get our first job, we're told to “be professional.” For many people, being professional means “leave your emotions at the door, leave who you really are, leave your humanity, leave the best part of yourself at home.” Then the other reason it's rare is because our parents tell us some version of, “If you don't have anything nice to say, don't say it at all.” Now, all of a sudden, as a leader, it’s your actual job to say something.

How can radical candor enable middle market managers and their teams/organizations to work more effectively?

Scott: If somebody is making mistakes and achieving results that aren't good enough, it does a disservice to that person and that person's growth, and also to the whole team, if that person is unaware of their mistakes and their underperformance. As a leader, regardless of the size of the company, it's your obligation to let people know when they're screwing up and also to let them know when they're doing great work. Care personally for people and challenge them directly. When you do this, people can fix mistakes or continue to do more great work so that other people know what success looks like.

People can't improve if they don't know when they're making a mistake. The only way that we improve is to know when something's good and also to know when it's bad. That’s where radical candor comes in.

Can you offer us an example where a lack of radical candor has led to bad results?

Scott: Earlier in my career, I started a software company. We had about 65 people and there was a guy on my team we'll call Bob [not his real name]. Bob was charming and a great colleague who was universally liked. Only one problem: Bob was doing terrible work. He would hand work into me with shame in his eyes. Yet I didn't have the courage to tell him that his work was bad because I liked him so much. In fact, I would say, “Bob, it's a really good start but maybe you can make it just a little better.”

Of course, he didn't improve. After 10 months, I realized that I had to fire Bob. When I was finished explaining to Bob where things stood, he pushed his chair back and looked at me, "Why didn't you tell me before? I thought you all cared about me!" It was probably the worst moment of my career. Ultimately, that software company failed because we had been ruinously empathetic with one another. We cared so much about each other that we failed to challenge each other, and that led to disaster.

Can you offer an example of “radical candor” helping someone grow?

Scott: Sheryl Sandberg was my boss when I worked at Google. I once gave a presentation to the founders of Google about the AdSense business, which I was then leading. Luckily, the business was on fire and I felt the meeting had gone very well. As I'm leaving the room, I walked past Sheryl and was expecting a high five, but she said, "Why don't you walk back to my office with me?" Sheryl told me the things that had gone well. Eventually, Sheryl told me, "You said ‘um’ a lot in there, were you aware of that?” I made a brush off gesture with my hand and said, “It's just a verbal tick. No big deal.” Sheryl said, "I know a really good coach who could help you and I bet I could get Google to pay for it." Again, I made the brush off gesture with my hand.

Sheryl stopped and looked me right in the eye, "I can see that I'm going to have to be more direct with you. When you say ‘um’ every third word, it makes you sound stupid." Now, with that bit of radical candor, Sheryl had my full attention. Some people might say Sheryl was being mean, but it was the kindest thing she could have done. If she hadn't said it in just that way, I wouldn't have gone to the coach and I wouldn't have learned that I really did say ‘um’ every third word. She had shown me in a thousand ways that she had my back and she actually offered to help. It was then that I realized that showing you care personally, at the same time that you're challenging directly, could be highly beneficial.

Why is the “platinum rule,” explained in the book, so important for middle market managers?

Scott: The platinum rule is not about “treating others as you’d like to be treated” [the golden rule] but is about understanding how other people want to be treated, and respecting that the way they want to be treated may differ from the way that you might like to be treated. As a manager, you need to make sure that you take the time and effort to get to know each of your direct reports well enough so that you can treat them the way they want to be treated. This requires deep conversations.

This”platinum rule” is especially important for caring personally. Sometimes, managers make the mistake of seeming aloof and not showing they care personally, but at other times managers might make the mistake of trying to be too intimate, too fast. This freaks people out. Caring personally is really about understanding the needs of other people and trying to adjust your approach accordingly.

What’s the best way for middle market managers to begin using “radical candor”?

Scott: As my example with Sheryl Sandberg shows, managers have to get comfortable giving and receiving feedback that cares personally and challenges directly. They need both to care and to challenge. If managers are too nice, as I was with Bob, that’s ruinous empathy. They need to challenge more. If you challenge directly, but don’t show that you care personally, that can come across as aggression -- so work on the caring part. Have more deep conversations with your people about their dreams and how you can support them in getting there. For more advice on how to do this, you can visit Candor, Inc. and use the tools there.