My journey to a place where we can begin to understand the unique needs of Black owners of middle market businesses.

Like so many of us, my journey began with my grandma.

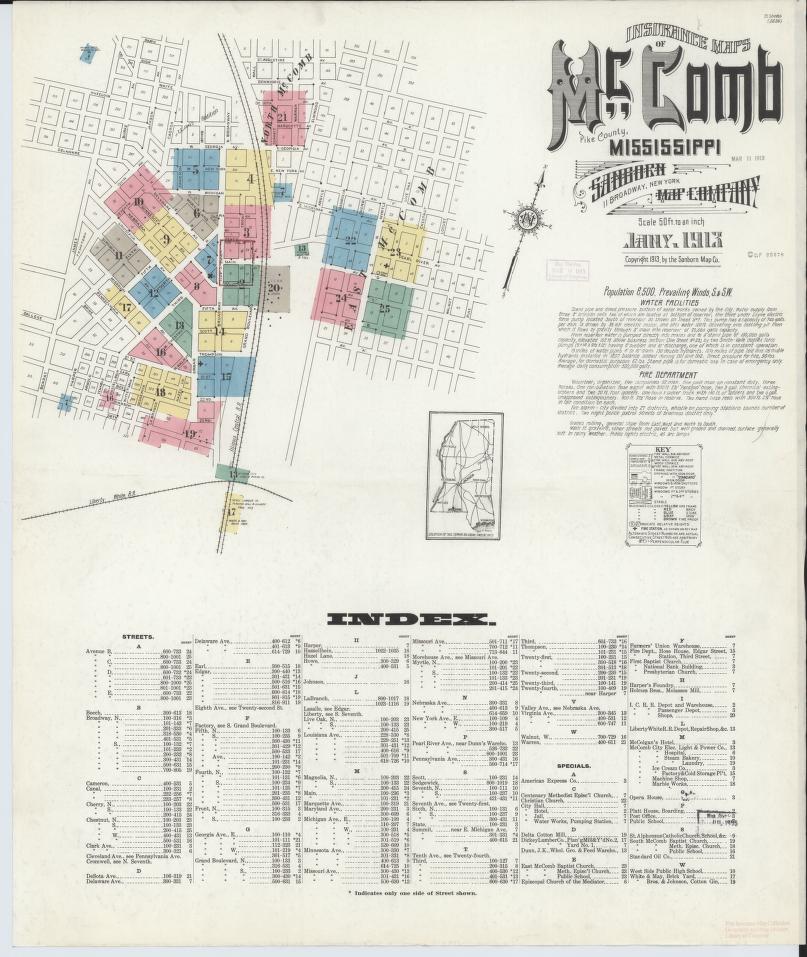

Evelyn grew up in the 1930’s and 40s in McComb, a segregated railroad town in southwestern Mississippi.

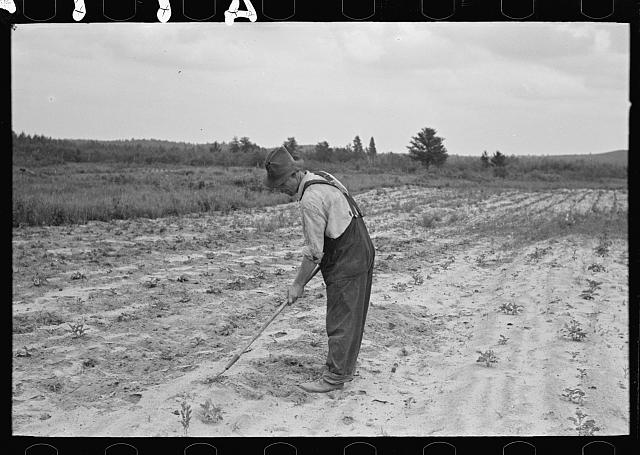

One day at age 12 or 13, as she was planting seed on the family farm, a car pulls up. A man gets out with a ruler. He had come to measure how far apart Evelyn had sowed the seed. Because according to Black codes – informal and formal systemic laws designed to keep Black people as second-class citizens – Black farmers like my grandma’s family were required to suppress their yields below those of white farmers. To enforce that, Black farmers were not permitted to plant their seed less than a foot apart, versus two inches for whites.

Black business owners still face inequity today. There have always been two doors to the American economy. And one of them, even if Black entrepreneurs pull themselves up by their bootstraps and persevere, leads to a passage rife with unique challenges, from access to multiyear corporate contracts and implicit bias in contract awards, to inequitable insurance/bonding requirements just for an opportunity to bid for new business, and sometimes elusive and hollow corporate supplier diversity contract programs that end up holding back their growth. As echoed by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, “From Reconstruction, to Jim Crow, to the present day, our economy has never worked fairly for Black Americans.”

It takes a lifetime to build a middle market company, one with annual revenue between $20 million and $500 million. It takes generations for a Black business owner to get to $2 or $3 billion in annual revenue. And perhaps only 50 Black families (in my estimation) can tell that story today.

*

In 2021, there were only five publicly traded, majority-Black-owned firms. That compares with approximately 4,000 publicly traded companies in the United States in 2024. Think about that for a minute.

Data like that, while stunning, does not shed much light on why there aren’t more $100-million Black-owned businesses and publicly traded companies, let alone what the U.S. economy could look like with more Black-owned firms.

Here’s a few of the many factors I’d like to amplify regarding the historical whys behind the data:

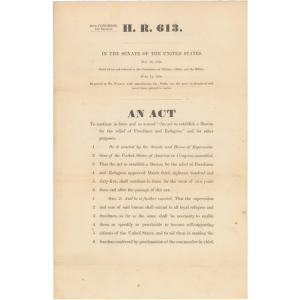

- The formation of Black-owned business in the U.S. has been historically delayed. You won’t find many Black firms active today with roots earlier than the 1940s for many reasons, including exclusion from fair financial markets, inherent and disparate distribution of federal economic programs commencing with the Freedmen’s Bureau Act in 1865, land theft, stolen innovations, forced land sales called partitioning, and racial violence.

- An Institute for Justice study shows that between 1949 and 1973, 2,532 eminent domain projects in 992 cities displaced 1 million people – two-thirds of them Black.

- An Associated Press (AP) investigative series, published in 2001, reported that hundreds of Black landowners lost more than 24,000 acres, including stores and city lots — worth tens of millions in today’s dollars — through unethical legal tactics and racial violence between the Civil War and 2001.

- In 1910, the AP reported, Black Americans owned at least 15 million acres (6 million hectares) of farmland, nearly all of it in the South, according to the U.S. Agricultural Census. Today, Black Americans own only 1.1 million acres (440,000 hectares) of farmland and are part owners of another 1.07 million acres (428,000 hectares).

- Until the civil rights struggle of the 1950s and 60’s, Black Americans were powerless to prevent the taking of their farmland, according to Stuart E. Tolnay, a University of Washington sociologist, interviewed by Associated Press.

- In recent times, the whys behind the dearth of $100-million Black-owned businesses and publicly traded companies is tied more to policy, such as federal rules that require the inclusion of Black-owned firms in government and diversity contracting programs (i.e., affirmative action) that have come under fire, and lack of institutional knowledge within Black families: Where do you turn for trusted advice about growing your company when no relatives are Fortune 500 CFOs, CEOs, or investment bankers or have even worked in corporate America?

- Another why is that while supplier diversity programs may initially spur business, they may ultimately limit Black-owned firms’ growth, as sometimes lucrative procurement decisions are made with business decision-makers that sit outside the supplier diversity channel.

- The federal government’s efforts to bolster the inclusion of Black-owned businesses in contracting have come under attack from multiple fronts. The legal landscape, political environment, economic stress, and technological and market changes are all influencing the scope and focus of federal contracting programs and make their outlook dynamic and uncertain.

- Historically, diverse-owned businesses, including Black-owned firms, have been underrepresented as primary contractors in federal procurement. The cost of entry to some supplier diversity programs is so high and complex that Black-owned firms do not qualify for various opportunities. As a result, Black-owned companies are far too often subcontractors and seldomly the prime awardee.

As head of the Black/African American Segment for Wells Fargo Commercial Banking, I am on a journey, striving for the commercial banking industry to be in a place where we understand the “whys” and the unique needs of Black owners of middle market businesses.

*

Back in 2021, as the inaugural leader of the Black/African American Segment for Wells Fargo Commercial Banking, I heard about sustainability and sustainability-linked bonds, which are designed to encourage capital flows to green and social projects or offer favorable terms, such as lower interest rates compared with traditional bonds, among other benefits. And I wanted to learn more. I was excited to learn about innovative financial products that centered around diverse communities.

In discussing these options at a meeting, I had great optimism and hope for offering up a specific product solution for diverse owners, but as each minute of our conversation passed, I experienced a full spectrum of responses and corresponding emotions, concluding with disappointment: “So wait, this bond product rewards corporations for achieving certain social milestones such as retaining a diverse work force, but there are no incentives for diverse business owners to stay in business?” The question caught everyone off guard, but a beautiful moment presented itself with the follow-up question, “Moses, can you please provide data and insight into the varying experiences of diverse – more specifically Black – business owners in the middle market?”

In the moment, I was well-equipped to cite disparate treatment of Black people, ranging from Black infant mortality, home ownership, mass incarceration, gun violence, student loan debt, food deserts, Black-white wealth gap, and access to capital constraints on Black-owned business with revenues under $5 million. However, I was not prepared to speak to data on the overlooked experience of Black owners of middle market businesses and the need for equitable product solutions.

I left the meeting motivated. I knew we needed more tools. We needed data. Wall Street understands data. Industry titans and executives at Fortune 100 firms make decisions with data, not anecdotes. To move the needle with product innovation, I need to be able to articulate to stakeholders the quantifiable outcomes of a new financial product and how said product will benefit the Black middle market community, while taking into consideration the accompanying risk profile. As the sustainability-linked bonds require the achievement of agreed upon milestones in exchange for incentives, the industry needs supplemental and tangible data points that speak to and connect directly with the Black middle market experience.

That meeting three years ago ultimately led to the reason I’m writing today: to announce a forthcoming report from the National Center for the Middle Market (NCMM), in partnership with Wells Fargo, that does something never been done before: focusing on the Black middle market and uncovering its unique story.

All the research about Black business before this has centered on small business, generally speaking. No one has been or is talking about the Black middle market. In my time working in commercial banking, I often used NCMM reports from which to glean industry insights and sentiments. Given NCMM’s deep understanding of middle market dynamics and research track record, I knew this organization would be the right partner to prepare a first-of-its-kind report on the Black middle market.

The “

2024 Insights and Perspectives from Black Leaders in the Middle Market,” is a first step in documenting the nuances and experiences of Black-owned middle market firms in the U.S. Moreover, this report seeks to amplify major advocacy points to the commercial banking industry and procurement supply chains and ask how can we design equitable pathways together.

This is my life’s work: building upon the barriers overcome by our ancestors and raising the bar for the historically underrepresented and underutilized Black middle market. I may not be the financer that gets the Black middle market to where it needs to be, but I want to be faithful in running my leg of the race for policy expansion and product innovation accelerating upward mobility for Black business owners.

I’m excited to share our findings – it’s the first step in building those tools. And we’re excited to begin a national conversation about the Black middle market. Please join us on this journey and be an active ally in supporting the growth of Black middle market businesses.

Moses Harris is a senior vice president and the Black/African American Segment leader for Wells Fargo Commercial Banking, where he has worked 14 years. He earned an M.B.A. from California State University, Fresno. Harris is based in Los Angeles, where he lives in the Studio City. He volunteers as an entrepreneurship and financial literacy instructor for the nonprofit 100 Black Men of Los Angeles. He serves on the boards of AmPac Business Capital, a nonprofit lender to small businesses, and the NASDAQ Entrepreneurial Center. He can be reached at moses.harris@wellsfargo.com

The views expressed present the opinions of the author on prospective trends and related matters in middle market banking trends as of this date, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Wells Fargo & Co., its affiliates and subsidiaries.

Sources:

National Action Network’s Annual King Day Breakfast. Jan. 17, 2022, Washington, D.C. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0557

The fintech company TiiCKER in 2021 compiled a list of publicly traded, majority Black-owned firms: Axesome Therapeutics, Inc.; Carver Bancorp., Inc.; Global Blood Therapeutics, Inc.; RLJ Lodging Trust; and Urban One, Inc.

Number of Public Companies v. Private: U.S. | Advisorpedia

“Eminent Domain & African Americans: What is the Price of the Commons?” by Mindy Thompson Fullilove, MD. Volume 1 of Perspective on Eminent Domain Abuse. fullilove v-2.indd (ij-org-re.s3.amazonaws.com)

'When They Steal Your Land, They Steal Your Future' - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com), Part 1, by The Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay of Associated Press, as published in Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 2001.

'When They Steal Your Land, They Steal Your Future' - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com), Part 1, by The Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay of Associated Press, as published in Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 2001.

'When They Steal Your Land, They Steal Your Future' - Los Angeles Times (latimes.com), Part 1, by The Todd Lewan and Dolores Barclay of Associated Press, as published in Los Angeles Times, Dec. 2, 2001.