As of this date—October 2017—the U.S. economy has expanded

for one hundred consecutive months. That is the third-longest

period of uninterrupted growth in U.S. economic history. The

longest, 120 months, came in the 1990s; the expansion of the

1960s lasted 106 months. The current expansion has not been

rapid; no one would call it a boom. It has not been evenly

distributed across places and populations. But it has been

extraordinarily long-lived.

It has also been led by middle market companies. In the last

five years, non-farm employment in the United States has

increased from 142 to 154 million—roughly eight percent. The

middle market has added jobs at a rate of 5.5% a year. That

figure includes inorganic growth, so it is not apples-to-apples

with overall employment. But quarter after quarter, comparable

data show middle market employment rising at least twice as

fast as employment in smaller or bigger companies. The same

holds for top-line growth, which for the middle market has

dipped below 6% only four times in the last 20 quarters.

We have noted before how benign the economic climate has

been, with negligible inflation, persistently low costs for capital,

talent, and energy, and robust equity markets. (This this is the

second-longest bull market in history.) Microeconomic signals

are green, too. Executives expect profits to rise faster than

costs. Forty-one percent of companies say their new-order

pipeline has grown, a number that is 10 full percentage points

higher than it was at this time in 2016. Among those with fuller

pipelines, the average increase is a very robust 13.2%.

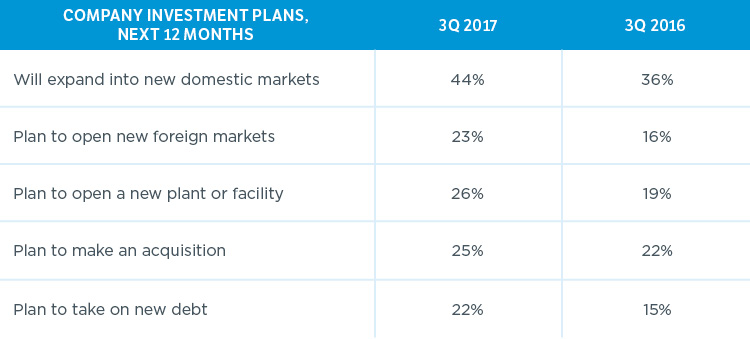

Given all this, it is no wonder that middle market executives

expressed this quarter their highest-ever level of confidence

in their local economies, second-highest ever confidence in

the global economy, and third-highest-ever confidence in the

U.S. economy. They also say that they will back that confidence

with actions designed to secure and extend their growth.

These are plans, not promises; but historically middle market

companies have kept close to plan. For example, a year ago

37% planned new domestic expansion, and 36% actually did it.

This worm will turn; worms always do. While the middle market

does not seem to face macroeconomic headwinds, there are

considerable uncertainties. Company valuations, sovereign

debt, and political risk all are high. Trade agreements are being

challenged. These or other factors could put an end to the

good times, and they will be obvious only in retrospect, and

out of executives’ hands. Two major challenges are more under

executives’ control.

The first challenge: Talent shortages. Four out of 10 executives

say a lack of talent constrains their growth. Executives cannot

do much about workforce participation rates, which are

affected by factors like an aging population, immigration, and

labor lost to opioid addiction. But only 35% of middle market

job vacancies are filled by promotion from within, which

suggests companies experiencing labor shortages should

rely less on the tight outside labor market and invest more in

training, developing career paths for employees, and enhancing

the employee value proposition to increase retention.

The second challenge: The middle market, like the rest of the

economy, is not getting much in the way of labor-productivity

improvement. For the last two quarters, revenue growth

and employment growth have converged. In 2014, we noted

that job growth was trailing revenue grow substantially—in

the third quarter of 2014, the two numbers were 7.5 and 3.5,

respectively. At that time we wondered if executives were

being too cautious about hiring. Now it appears that they are

getting fewer gains in productivity than they should—perhaps

an indication that they are holding back on capital spending.

The paradox: If they could solve the productivity problem, they

would also reduce the talent-shortage problem.